Below is an article from Nicholas Workskett of Bellmans Auctioneers who has provided a Valuation of the Bishop Henry King Bequest, housed within the Cathedral's Library.

… At common graves we have Poetique eyes

Can melt themselves in easie Elegies,

Each quill can drop his tributary verse,

And pin it, like the Hatchments, to the Hearse:

But at Thine, Poeme, or Inscription

(Rich soule of wit, and language) we have none.

Indeed a silence does that tombe befit,

Where is no Herald left to blazon it. …

Henry King, ‘To the Memorie of my ever desired friend Dr Donne’

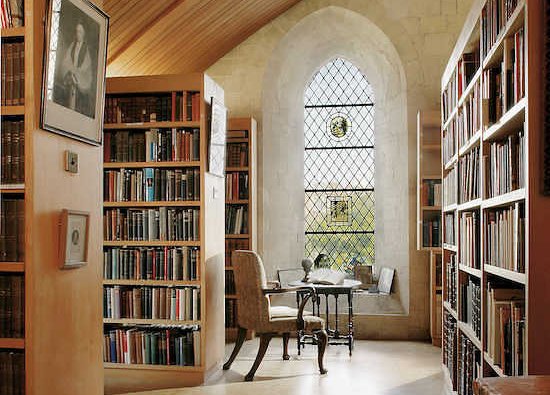

The library of Chichester Cathedral is, arguably, less well-known than it deserves to be. This may be explained, at least in part, by its relative inaccessibility. The intrepid visitor, having first located a door in a corner of the Treasury, must then negotiate an admittedly enticing but very steep and narrow spiral stone staircase which will eventually lead to another door at its summit and, at last, to the library itself. The library is therefore not as readily accessible to casual visitors to the Cathedral as some of its more conspicuous glories, notably the Arundel Tomb (movingly memorialised by Philip Larkin), the 12th-century Chichester Reliefs, the Roman mosaic or the striking John Piper tapestry which hangs, or rather explodes in colour, at the High Altar.

The library occupies a 12th- or early 13th-century room which was, almost certainly, built to house it. Its interior is notable for the early 12th-century carvings which originally formed part of the corbel-table running around the exterior of the Cathedral. The corbels therefore pre-date the room which now encloses them. These rudely carved blocks of stone display all the fearful and unfettered imagination of the earlier Medieval period. In one, a human figure is floundering in the jaws of a monster; in another, a demon whispers into a man’s ear; and, in a third, a man is shown suffering from toothache, his hands splayed on his swollen cheeks and his mouth wide open, as if crying out in pain. Since the 19th-century, we have tended to romanticise all things Medieval (the Pre-Raphaelites were chiefly to blame, with their noble knights and willowy damsels), but – for all that remote era’s mighty Cathedrals, the potency of its art, its chivalry and courtly love, the tales of King Arthur and the poetry of Chaucer – you can’t help thinking that this unfortunate fellow with the molars would have gladly traded it all for 500mg of Paracetamol.

The Bishop Henry King bequest of approximately 300 books occupy their own pair of 19th-century bookcases in a corner of the room by a window which gives a vertiginous view of the nave. In the library’s atmospheric shadows, it would be quite easy to miss these bookcases or the importance of the books they contain. On my second day, I took the precaution of arming myself with a torch.

The non-Bishop Henry King books in the library form by far its greater part, at least in quantity, and were listed and valued, very ably, by Rose Sanguinetti in 2015. While these books are not the concern of this article, I feel I must mention one highlight, a book which would appeal to the cartographer rather than to the theologian: a fine copy of Caius Julius Solinus’s Polyhistor (Vienna, 1520), bound in contemporary calf. The book is important for its double-page world map by Peter Apian which is one of the earliest to include that magical word ‘America’.

As one would expect, Cathedral libraries tend to be rich in theological works and the library at Chichester is no exception. However, in its general holdings, it also contains, inter alia, books on English history, topography (chiefly the topography of Sussex), architecture, law, history, numismatics and bibliography. In contrast, the Bishop Henry King portion of the library is almost exclusively theological, the most widely represented author, with a total of eight books to his name, being Jean Calvin. There are also eight bibles, ranging from one printed in Latin in Lyon in 1526 to a Polyglot bible printed in Basle in 1618. Of the c. 300 books, I identified only a handful which could be said to be exclusively secular. These include Plautus’s Opera (Paris, 1576), a collection of the Roman playwright’s surviving plays; Jeremiah Wilde’s De formica [‘On Ants’] (Amberg, 1615); and Abraham Wright’s Delitiae delitiarum (Oxford, 1637),an anthology of poetry and epigrams, including one in praise of tobacco, taken from books which the compiler had consulted in the Bodleian Library.

Not a great deal has been written about the library, or the Henry King bequest, but, for the persistent researcher, some useful information can be obtained, usually in printed form rather than online (which makes a change). One of the earliest printed accounts of the library appears in Beriah Botfield’s Notes on the Cathedral Libraries of England (1849), in which the author notes with approval the fine bookplates found in many of the books. Also very helpful is Francis W. Steer’s Chichester Cathedral Library (1964), published, in pamphlet form, by Chichester City Council. It includes some excellent photographs including close-ups of many of the corbels. Geoffrey Keynes’ Bibliography of Henry King (1977) includes a list of John Donne’s books in the library, as does his article ‘Books from John Donne’s Library’ in Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society (Vol. 1, No. 1, 1949). Without doubt, however, we owe our greatest debt of gratitude to Mary Hobbs, both for her fascinating article in The Book Collector (vol. 33, no. 2, Summer 1984) entitled ‘Henry King, John Donne and the Refounding of Chichester Cathedral Library’ and for a chapter dedicated to the library in her Chichester Cathedral: An Historical Survey (1994). More recently, Matthew Dimmock [et al.] gives an account of the library in his Art, Literature and Religion in Early Modern Sussex (2014). A rudimentary list of the Henry King books does exist, but it neglects to mention any of the books’ associations, and does not include values.

So who was Henry King? Born in 1592, he was educated at Westminster and Christ Church, Oxford and, after various clerical posts in London, Rochester, where he was Dean, and Colchester, where he was Archdeacon, served as Bishop of Chichester from 1642-46, through tumultuous times in our history. He was also a poet of note, although one now more anthologized than read, and he is often dismissed as ‘minor’, whatever that means. One modern critic is kind enough to qualify this assessment by conceding, ‘King was a minor poet of the age, but an excellent one among that class.’ So he was, at least, an excellent minor poet! The New Oxford Book of English Verse (1972), edited by Helen Gardner, contains just two of his works, the heartfelt, and heart-breaking, lament ‘Exequy upon His Wife’, perhaps his most famous work, and the much shorter and more abstractly elegiac ‘Sic Vita’.

Henry King was friends with several literary figures of his day, notably Ben Jonson and Izaak Walton (of The Compleat Angler fame); but, most significantly for our purposes, he was friends with John Donne, that principle star in the firmament of metaphysical poets. It is telling that the poem for which Henry King is chiefly remembered today, in addition to his ‘Exequy’, is his ‘To the Memorie of my ever desired friend Dr Donne’ which was first published in a posthumous edition of Donne’s works in 1633. King, who had held the position of Dean at St Paul’s between 1621 and 1631, commissioned a statue of Donne for the cathedral. Remarkably, it survived the great fire and can still be seen, complete with scorch marks to its base, in Wren’s Baroque edifice. King also acted as Donne’s executor, and, fortunately for Chichester, inherited several books from Donne which, in their turn, came to the Cathedral through King’s bequest following his death in 1669.

It is, of course, the John Donne associations which are of the most compelling interest for us. In the Henry King Library I found four books which unquestionably had once belonged to the poet. No one’s works from the Jacobean era – apart, perhaps, from Shakespeare’s – seem so alive and vivid to us as do Donne’s: his dilemmas, paradoxes, temptations and griefs are our own, and his sometimes conversational style, fusing passion and intellect, can seem very modern. It is impossible not to be moved when leafing through a book in the sure knowledge that it was once handled and read by one of our most revered poets. Thankfully, Donne was in the habit of signing his books with his distinctive compressed signature and his hand-written motto, and these are very welcome aids to identification. It is quite possible that there are other books of his in the collection which he did not sign or inscribe, but such speculations lie beyond the scope of this article. Donne’s motto is taken from the Italian of Petrarch and reads, ‘Per Rachel ho servitor & no[n] per Lea’. The consensus regarding its significance, for Donne, is that he had chosen a life of contemplation over one of action, which, of course, should be part of the job description for any self-respecting poet.

The four books which belonged to John Donne are Franciscus Balduinus’ Passio typica seu liber unus typorum veteris testament, qui passionem ac mortem domini ac salvatoris nostril Iesu Christi (Wittenberg, 1614), Alphonso Villagut’s Tractatus de rebus ecclesiae non rite’ alienates, recuperandis, atque in integrum restituendis (Bologna, 1606), Rodulphus Cupers’ Tractatus de sacrosancta universali ecclesia (Venice, 1588, containing, in addition to Donne’s signature and motto, his distinctive pencil marginal markings episodically throughout the text) and Jeremiah Wilde’s De formica (Amberg, 1615, a treatise on ants, with two other works bound in, similarly marked).

Usually, printed books are quite straightforward to value. Unlike paintings, for instance, or manuscripts, you will almost always find a precedent for pricing a book, whether it be a previous auction record or a dealer’s listing, on which to base a current replacement value. But how do you value a book which, by virtue of its association, is unique and irreplaceable? A book which not only came with the splendid provenance of the Bishop Henry King bequest but was also signed and inscribed by someone of the stature of John Donne? Remarkably few books signed by Donne have appeared at auction. I note, however, that a book signed and inscribed by him did come up at auction in 2019, but the highly reputable auction house which handled it – whose blushes I shall spare by not naming them – neglected to mention this small detail of its provenance in their description, although the catalogue illustration clearly shows Donne’s signature (scored through) and hand-written motto.

Among the more valuable books in the Henry King Library which do not have a John Donne association are three incunables, that is, books printed before 1501. Although it has been estimated that there were some nine million printed books circulating in Europe by the end of the 15th-century, they still generate a flurry of interest when they appear in the salerooms. It is worth noting, en passant, that incunables are the only books which are valuable by virtueof their date alone, irrespective of any other attributes they might possess.

A few of the books are signed by Henry King, an interesting example being John of Salisbury’s Policraticus (Leyden, 1595) which bears the inscription‘Henricus Kinge, ex Aede Xii [i.e. Christ Church], Oxon’ indicating that King would have owned this book when he was a student. Policraticus was written around 1159 and widely circulated in manuscript form before being first printed in Brussels in 1480. It is considered the first Medieval treatise on political thought, an example of the ‘Mirrors to Princes’ genre of books of which Machiavelli’s ‘Il Principe’ is perhaps the most celebrated, although atypical, example. The author is believed to have witnessed the murder of Thomas Becket.

The books are, of course, in the truest sense of the word, priceless, and it is very gratifying to know that they will remain in the safe-keeping of the Cathedral in perpetuity, for future generations to marvel at, study, and enjoy.

I spent a very happy few weeks in the library at the beginning of last year, just before Coronavirus reared its ugly head – relishing the Cathedral’s background sounds of bell, organ and choir as I worked – and I would especially like to thank Diana Wills, Sub-Librarian, and Canon Dan Inman, for making me feel so welcome.

Nikolaus Pevsner and Ian Nairn, in the Sussex volume of ‘The Buildings of England’ series, first published in 1965, sum up the charm of Chichester Cathedral perfectly, and provide a fitting epilogue to this modest essay: ‘Without any doubt it is one of the most lovable English cathedrals: that is partly the architecture, partly the way in which city and church flow together easily, partly the way in which the church authorities make you free of the cloisters and passages without harangue or stuffiness. It is a well-worn, well-loved, comfortable fireside chair of a cathedral.’ I can second that.

Nicholas Worskett, Bellmans Auctioneers

Find out more

In this short clip, the Cathedral's Canon Chancellor, the Reverend Dr Daniel Inman, explores Bishop Henry King's collection inside of the Cathedral Library.