On Rogation Sunday (5th May 2024) we welcomed Archdeacon of Brighton and Lewes, The Venerable Martin Lloyd Williams, as our Guest Preacher.

During this time of reflection and seeking blessings, his sermon delves into existential questions of belonging and purpose, drawing parallels between contemporary environmental crises and ancient struggles for identity. As the Cathedral continues its commitment to sustainability, the sermon calls for a deeper transformation toward a future where we coexists peacefully with the Earth. We invite you to listen to the sermon below.

"It's really, really good to be here with you on this Rogation Sunday. Can I, first of all, congratulate all here at the Cathedral for the incredible progress that has been made here at towards the goal of net carbon zero by 2030. I think you're leading the diocese, really, in this respect. So thank you for all of the efforts. I know these things are very much a team thing. So thank you to all who've participated in that. We're really grateful for the lead that you have given to us in this respect. It's really good to be part of something bigger. The environmental movement is definitely an opportunity for us to participate in something that is a lot bigger than any one of us or any one of our congregations. It's good to be part of that. I'd like us to think a little bit about that now. But first, let me just tell you a story about a farmer who lived on the border of Poland and Russia.

He wasn't sure whether he lived in Poland or in Russia. First of all, he got the Polish authorities to come and take a look, and they came with their maps and they surveyed the ground and they weren't sure. Then the Russian authorities came and they did the same. They came with their maps and they looked to see where he was. In the end, both sets of authorities came together and they decided, ‘Yes, dear farmer, you live in Poland’, to which he said with great relief, ‘Thank goodness, I won't have to go through another Russian winter’. Sometimes we wonder where we belong. We wonder quite how we fit. We wonder what bigger picture it is that we're part of. On a Sunday like Rogation Sunday, rogation is to ask God for things. We ask ourselves the question, Well, what are we asking God for? Because although this is traditionally about asking for God's blessing on the land, the things that we ask God for are very indicative of what's going on in the depths of our beings. Sometimes I ask my son, who has Down Syndrome, What do you want to do today? And invariably, he says, and I know the answer I'm going to get, which is why I asked the question, he says, ‘Can we go to McDonald's?’

So I think, oh, good. That means someone will have to go with you. But the things that we really want are the things that tell us quite a lot about ourselves. Now, in the Isaiah reading that we had, imagine if as a group of people, we had all been suddenly invaded by an alien power, and all of a sudden we've been carted off to another place, and we suddenly find ourselves asking these questions again,

Where do we belong? Who am I? What really matters?

All of a sudden, that crisis that befell the people of Israel as they were carted off to exile in Babylon suddenly focused their attention on those fundamental issues. And while the climate crisis that we face is not the same exactly as the crisis that befell the people of Israel, there is something about crisis as well that causes us to think, well, who are we? What is it that we really need? Where are we? We're really finding our security and our identity? What we ask for is incredibly illuminating. We are very much the products of the industrial revolution. We're very much the products of the enlightenment and of the reformation.

Certainly, over the past 500 years, these things have enabled human society in Western Europe, in North America and other places to make tremendous advances. But listening and talking with author and ethicist Claire Gilbert over the past week, she drew attention to some of what the historian Charles Taylor spoke of as a thing called buffering. Buffering is the way in which we have become cut off one another, where we see our relationships as one plus one plus one, rather than understanding ourselves in the sense that I am because you are. Claire also drew attention to the work of philosopher Martin Heidegger and his concept of Gestell. That's a concept which Heidegger described as the notion that nothing at all has any value, except that value which is given to it by human beings. That, as you can imagine, places us in a fairly scary place. It's resulted, consequently, in really no part of creation being entirely free from the impact of human beings, the atmosphere that we have impacted with greenhouse gases, the hydrosphere with dams and pollution, the lithosphere with mining, the pedosphere with farming, the biosphere that means all other species can only survive if they adapt to work around human beings and human life.

What people do we want to be is the question that is being asked. It's being asked by this passage in Isaiah. It's being asked by Jesus in the Gospels. It's being asked by all sorts of people today. The work of Taylor and Heidegger, these notions of buffering and of Gestell, point to a way of being that has, in many respects, delivered five centuries of human advancement. But it is premised on the notion that human beings have mastery and control over the planet rather than human beings living in harmony with the planet. It's an incredibly anthropocentric way of looking of things. I would contend it is not a mindset that leads to human joy, human freedom, or indeed human peace. It's a mindset. It's not a mindset that is really resonant with the prophecy, the vision of Isaiah, his amazing vision, that you shall go out with joy, you will be led forth in peace, and the mountains and the hills will burst forth before you. The trees of the field shall clap their hands. Nowadays, we're not really quite sure what to do with passages of that sort. But imagine if you were in captivity in Babylon and you heard those words and you were given that hope and you were encouraged to think that actually you might still have a future, and the future would be a future of being in harmony with creation and with humankind.

There's a new exhibition that started, I think last week at Kew Gardens, by the artist Mark Quinn. I haven't seen it yet, but I certainly do intend to go and see it. One of the things that he's allowed to happen is he's allowed a bonsai tree to be able to grow naturally without the restrictions that keeps bonsai trees normally very small. It's now grown to 5 feet tall. And so he's asking us the question. He's asking the question How do you know when you're looking at something natural and when you're looking at something artificial? We've become so particularly stuck in one way of looking at the world and of looking at the things that are around us, that sometimes we really struggle to tell the difference between what is artificial and what is natural. I don't know how many of you here are devotees of Clarkson's Farm. If you are, you may have started to watch Series 3. I'm a devotee and it only dropped on Friday, so I've only so far had a chance to see a couple of episodes. However, it is interesting to see that Caleb, Jeremy Clarkson's Farm Manager, is very sceptical about a new way of farming that plants wheat and beans together in the same field.

I've lived on this land all my life, he said, and that drill won't work and this process won't work. I won't give you any spoiler alert at this stage, but it's very interesting to see what happens. How do we look on the world? Can we look on it with fresh eyes? Throughout human history, all sorts of people have been able to look at the world in different ways. Emily Brontë said, ‘Every leaf speaks bliss to me’. What a beautiful thing to say. But behind that, what person is able to say that? Elizabeth Barrett-Browning, I'm sure you know her famous poem, which includes the verse, Earth is crammed with heaven and every common bush, a fire with God, but only those who see take off their shoes. And Julian of Norwich, And God showed me something small, no bigger than a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, and I perceived that it was as round as any ball. I looked at it and thought, what can this be? And I was given this general answer, it is everything that is made. I was amazed that it could last, for I thought it was so little that it could suddenly fall into nothing.

I was answered in my understanding, it lasts and always will last because God loves it, and thus everything has been through the love of God. What people do we want to be? What planet do we want to inhabit? One that we can subdue in a mad fit of human supremacism. Or do we want to live in a planet where we are able to live truly in harmony? And so, Isaiah's vision asks the same question, what are you spending your money on? He asks. How unbelievably relevant. What are you labouring for? He asks. Rather, he says, if you are thirsty, come to the waters. Come and buy the really good stuff that actually you don't even need money for. We think, well, free stuff like that can't be worth very much. Delight yourselves, says Isaiah, in the best of things which is found in what scripture calls covenant or gift and relationship. We think it can't be true, but God says in this passage in Isaiah, my ways are not your ways. My ways are higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts. And so at the heart of all of this is the deep need to enter in, to covenant relationship with God and with the Earth and with one another, to allow something to happen in our lives that jolts us out of the way that we have seen things for so long and enables us to get through the barriers of fear, to be able to live freely, peacefully and joyfully.

That's what this vision of the environmental movement is actually all about. Finally, we do so remembering the words of Jesus, Saying that this isn't a movement which is about violence or is about creating more enemies, but we do so in a way that follows the command of Jesus. I am giving you these commands so that you may love one another. We could spend hours talking about that, but for today, we continue with this movement in the spirit of Jesus who says, Love one another. I really do wish you well in all of the cathedrals endeavours to get to net carbon zero. Thank you for all that you are doing. There is so much science that we can, I don't know, we can read out, we can become aware of. But sometimes it's in our hearts that we know things really need to change. It's in the people we want to be. It's in the world we want to create. And fundamentally, that is an issue of the heart. And Jesus wishes to touch our hearts so that we can truly reflect his glory throughout all creation. Amen."

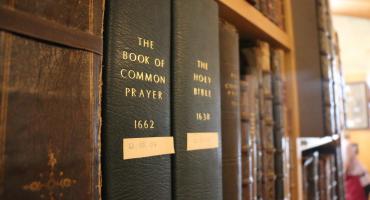

Header image: @buttercup.photo